The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain, encapsulates a transformative period in American history from the 1870s to the early 1900s. This era, marked by rapid economic growth and industrial expansion, reveals a fascinating juxtaposition between opulence and hardship. As the United States emerged as a global industrial power, the landscape of society underwent profound changes, shaping the lives of millions and laying the foundation for modern America.

During this remarkable time, technological advancements and corporate growth redefined the American economy, while urban centers swelled with immigrants seeking opportunity. Yet, beneath the shimmering surface of wealth and progress, stark inequalities and social struggles unfolded, prompting the rise of labor movements and a quest for social justice. The Gilded Age serves as a pivotal chapter in understanding the complexities of American society, reflecting both the ambitions and challenges that accompanied its ascent.

The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in their 1873 novel, represents a transformative period in the history of the United States, roughly spanning from the 1870s to the early 1900s. This era was characterized by rapid economic expansion, industrial growth, significant social changes, and a profound reshaping of American society. Understanding the Gilded Age requires a detailed examination of its defining features, historical context, and significance, as it laid the groundwork for modern America.

The term "Gilded Age" suggests a superficial layer of gold covering a less attractive reality beneath. This metaphor captures the duality of the period, which saw immense prosperity juxtaposed with stark social issues. The Gilded Age was marked by the explosive growth of industry, urbanization, and the rise of a capitalist economy that favored the wealthy elite. A few industrialists, often referred to as "captains of industry" or "robber barons," amassed unprecedented wealth and power, while many Americans struggled against poverty and exploitation.

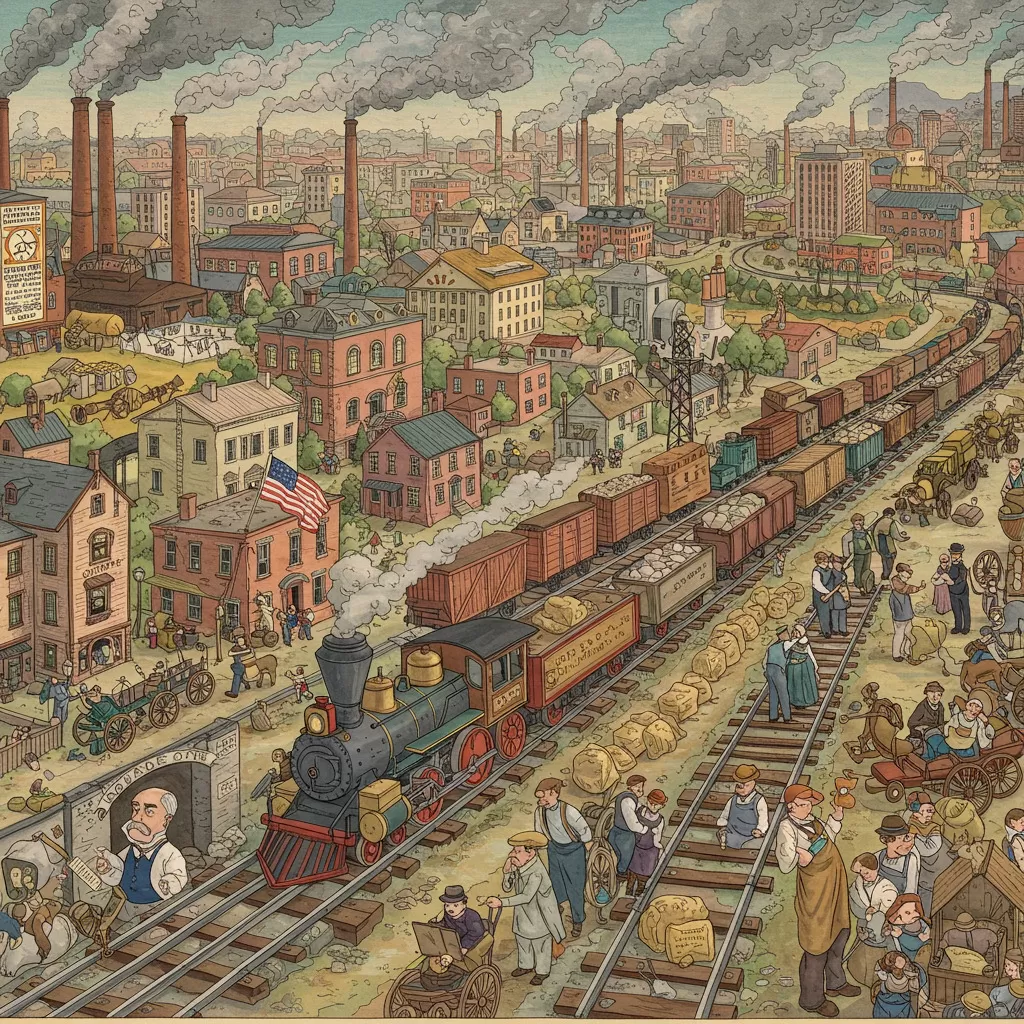

The Gilded Age was not merely an era of economic transformation; it was also a time of significant technological advancements. The introduction of new machinery, the development of assembly lines, and the expansion of railroads revolutionized production methods and reshaped the American workforce. This led to a shift from an agrarian economy to an industrialized society, where factories became the new centers of economic activity.

Furthermore, the Gilded Age was a period of cultural transformation. It witnessed the flourishing of new art forms, literature, and social commentary, which echoed the complexities of the time. It was a time when American society grappled with its identity, values, and the implications of its rapid modernization.

The Gilded Age must be understood in the context of the post-Civil War United States. The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked a significant turning point, as the nation began to rebuild and expand its economy. The aftermath of the war saw a massive influx of immigrants, many of whom were seeking better opportunities. This migration fueled urban growth and provided the labor force needed for burgeoning industries.

Additionally, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 connected the east and west coasts, facilitating trade and migration. The railroad industry itself became a catalyst for economic expansion, enabling other sectors to flourish. The Gilded Age was also characterized by a lack of regulatory frameworks, which allowed businesses to operate with minimal oversight. This environment led to monopolistic practices, as corporations sought to eliminate competition and maximize profits.

The significance of the Gilded Age lies not only in its economic achievements but also in the social consequences that followed. The era highlighted the stark divide between the wealthy elite and the struggling working class, leading to social unrest and labor movements that sought to address these disparities. The period set the stage for future reforms, including the Progressive Era, which aimed to tackle the issues that had arisen during the Gilded Age.

In this way, the Gilded Age serves as a critical chapter in American history, illustrating the complexities of progress and the challenges that accompany rapid change. Its legacy continues to resonate, as the dynamics of wealth, power, and social justice remain central to contemporary discussions about the American experience.

The Gilded Age, spanning from the 1870s to the early 1900s, represents a time of profound economic transformation in the United States. This era is characterized by rapid industrialization, expansion of the railroad network, and the rise of large corporations that reshaped the economic landscape of the nation. This section delves deep into these elements, exploring the rise of corporations, technological innovations, and the significant impact of railroads on the economy.

At the heart of the economic expansion during the Gilded Age was the dramatic rise of corporations. The corporate form of business organization allowed for the accumulation of capital on an unprecedented scale, facilitating the establishment of large enterprises that dominated their respective industries. With the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868, corporations were granted the same legal rights as individuals, thus paving the way for their proliferation.

One of the most prominent figures of this era was John D. Rockefeller, whose Standard Oil Company exemplified the power and influence of corporations. Rockefeller implemented practices such as horizontal integration, where he bought out competitors to monopolize the oil industry. By the turn of the century, Standard Oil controlled over 90 percent of U.S. oil refining. This monopoly not only shaped the oil market but also influenced regulatory practices and economic policies.

Similarly, Andrew Carnegie's Carnegie Steel Company revolutionized the steel industry through vertical integration. Carnegie acquired all aspects of production from raw materials to distribution, drastically reducing costs and increasing efficiency. His success in the steel industry underscored the potential of corporate strategies to drive economic growth and innovation.

The rise of corporations was not without its challenges. By consolidating power, these entities often faced backlash from smaller businesses and the public. The sheer influence wielded by figures like Rockefeller and Carnegie led to growing concerns about monopolistic practices, prompting calls for regulation and the eventual establishment of antitrust laws in the early 20th century.

The Gilded Age was also marked by groundbreaking technological advancements that fueled industrial growth. Innovations in machinery, manufacturing processes, and transportation fundamentally altered the economic landscape. One of the most significant technological developments was the introduction of the assembly line, which was popularized by Henry Ford in the early 20th century but had its roots in earlier manufacturing techniques.

In addition to manufacturing advancements, the era witnessed the emergence of new technologies that transformed transportation. The invention of the telegraph in the 1840s and the telephone in the 1870s revolutionized communication, facilitating faster decision-making and coordination in business operations. The importance of these innovations cannot be overstated, as they laid the groundwork for a more interconnected economy.

The transportation sector, in particular, experienced dramatic changes during the Gilded Age. The expansion of the railroad network was pivotal in promoting economic growth, as it connected previously isolated regions, allowing for the efficient movement of goods and people. Railroads became the backbone of the American economy, providing the infrastructure necessary for industries to flourish.

The development of the transcontinental railroad was a monumental achievement of this era. Completed in 1869, the railroad linked the eastern U.S. with the West Coast, opening vast new markets for goods and resources. The ability to transport agricultural products from the Midwest to urban centers and manufactured goods to remote areas transformed trade patterns and stimulated economic activity across the nation.

The impact of railroads on the economy during the Gilded Age can hardly be overstated. Railroads not only facilitated the movement of goods but also played a crucial role in the expansion of industries such as coal, steel, and agriculture. The demand for steel rails and coal for locomotives created a symbiotic relationship between the railroad industry and other sectors of the economy.

Moreover, railroads contributed significantly to the urbanization of the United States. As cities grew around key rail hubs, populations shifted from rural areas to urban centers in search of employment opportunities. This migration fueled the labor market, providing a steady supply of workers for factories, which in turn supported industrial growth.

Despite the benefits brought by the railroads, the industry faced its share of challenges. The rapid expansion led to overbuilding, and many railroads struggled with financial instability. The Panic of 1893, a severe economic depression, was partly triggered by railroad bankruptcies, which highlighted the vulnerabilities within the industry.

In response to the challenges faced by the railroad industry, the government began to intervene more actively in the late 19th century. The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 was a landmark piece of legislation aimed at regulating the railroad industry and curbing monopolistic practices. The establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) marked the federal government’s first effort to regulate private industry, setting a precedent for future regulatory measures.

In summary, the Gilded Age was a pivotal period of economic expansion and industrial growth in the United States. The rise of corporations, coupled with innovations in technology and transportation, transformed the American economy, leading to unprecedented levels of production and efficiency. Railroads played a crucial role in this transformation, connecting regions and promoting urbanization. However, the era was also marked by challenges, including financial instability and growing public concern over monopolistic practices, which prompted the beginnings of regulatory efforts that would shape the future of American business.

| Key Figures | Industry Impact |

|---|---|

| John D. Rockefeller | Monopolized the oil industry with Standard Oil. |

| Andrew Carnegie | Transformed the steel industry through vertical integration. |

| Henry Ford | Introduced assembly line production techniques. |

| Interstate Commerce Commission | Regulated railroads to prevent monopolistic practices. |

The Gilded Age, spanning from the 1870s to the early 1900s, was not only marked by economic transformation but also by significant social changes and labor movements that reshaped the American landscape. As industries flourished, cities became melting pots of cultures and diverse populations, leading to profound shifts in the social fabric of the nation. This period saw a surge in immigration, urbanization, and labor activism as workers began to organize for their rights amidst harsh working conditions and economic inequality. The following sections delve into the intricate dynamics of immigration and urbanization, the rise of labor rights and strikes, and the formation of labor unions during this transformative era.

The Gilded Age experienced a dramatic increase in immigration, largely fueled by economic opportunities and social unrest in Europe. Millions of immigrants poured into the United States, seeking a better life and the promise of prosperity. The primary waves of immigrants during this period came from Southern and Eastern Europe, including countries such as Italy, Poland, and Russia, as well as from Asia, particularly China and Japan. By the turn of the century, cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco transformed into bustling urban centers, with their populations swelling due to the influx of foreign-born residents.

Immigration brought a diverse array of cultures, languages, and traditions to the United States. However, it also led to significant challenges, including the struggle for assimilation and the rise of xenophobia. Immigrants often faced discrimination and hostility from native-born Americans, who viewed them as a threat to jobs and cultural values. This tension fueled social divisions and prompted various legislative measures aimed at restricting immigration, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the country.

Urbanization was not merely a byproduct of immigration; it was also a reflection of the industrial boom that characterized the Gilded Age. As factories proliferated, people migrated from rural areas to cities in search of work. This rapid urbanization led to overcrowded living conditions, with many immigrants settling in tenement buildings that offered little in terms of sanitation or safety. The poor living conditions in these urban settings highlighted the stark contrast between the wealthy elite and the struggling working class, laying the groundwork for social unrest and labor movements.

The rise of industrialization during the Gilded Age resulted in the creation of numerous factories and mills that employed vast numbers of workers. However, these jobs often came with grueling hours, low wages, and unsafe working conditions. The exploitation of labor became a pressing issue, leading to an increasing awareness among workers about their rights. Labor activism began to take root as workers sought to improve their circumstances through organized efforts.

Strikes became a common method for laborers to voice their grievances and demand better treatment. Notable strikes during this period included the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which was triggered by wage cuts and rapidly escalated into a nationwide protest. Workers from various industries joined forces, leading to violent clashes in multiple cities. The strike marked a significant moment in American labor history, as it showcased the potential power of collective action.

Another pivotal event was the Haymarket Affair of 1886, which began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour workday in Chicago. However, the situation turned violent when a bomb was thrown, resulting in the deaths of several police officers and civilians. The aftermath led to a crackdown on labor organizations and a heightened perception of labor movements as radical and dangerous. This event illustrated the volatility of labor relations during the Gilded Age and the lengths to which workers were willing to go to fight for their rights.

In response to the challenges faced by workers, labor unions began to emerge as vital organizations advocating for workers' rights. The National Labor Union (NLU), founded in 1866, was one of the first attempts to unite workers from various trades. Although it ultimately dissolved in the 1870s, it laid the groundwork for future labor movements. The Knights of Labor, founded in 1869, was another significant organization that sought to unite skilled and unskilled workers across different industries. The Knights advocated for broad social reforms, including the establishment of an eight-hour workday, equal pay for equal work, and the abolition of child labor.

Despite facing opposition from employers and government authorities, labor unions gained momentum throughout the Gilded Age. The American Federation of Labor (AFL), established in 1886, focused on skilled workers and aimed to improve wages, working conditions, and hours through collective bargaining. The AFL's pragmatic approach allowed it to achieve significant successes in negotiating labor contracts and securing better conditions for its members.

Labor unions faced numerous challenges, including violent confrontations with law enforcement, the use of strikebreakers, and the negative portrayal of unions in the media. However, the growing awareness of workers' rights and the need for representation led to increased support for labor movements. The labor struggles of the Gilded Age set the stage for future advancements in labor rights and the eventual recognition of unions as essential stakeholders in the American workforce.

The social changes and labor movements that characterized the Gilded Age were instrumental in shaping the future of the United States. The struggles of workers and the rise of labor unions laid the foundation for the advances in labor rights that would follow in the 20th century. As the nation evolved, the lessons learned from this tumultuous period continued to resonate, influencing the trajectory of labor relations and the ongoing quest for social justice.

The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain, refers to a period of significant transformation in the United States between the late 19th century and the early 20th century. This era is characterized by remarkable economic growth, industrial expansion, and a notable increase in wealth for a select few. However, beneath this facade of prosperity lay deep social issues, marked by considerable wealth disparity, poverty, and the emergence of social reform movements. This section will explore the emergence of the new rich, the stark realities of poverty and living conditions, and the influence of philanthropy during this transformative period.

During the Gilded Age, the term "new rich" came to define a burgeoning class of wealthy individuals who amassed their fortunes through industrialization, speculation, and entrepreneurship rather than inheritance. This new elite, often referred to as "robber barons," included prominent figures such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan. These men played pivotal roles in shaping America’s economic landscape, monopolizing industries and amassing substantial wealth.

Carnegie, for instance, revolutionized the steel industry with his innovative production techniques and business practices, ultimately leading to the creation of the Carnegie Steel Company. Similarly, Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company dominated the oil industry, employing aggressive strategies to eliminate competition and establish a monopoly. The wealth generated by these industrial giants was staggering; by the end of the 19th century, Carnegie was one of the richest men in the world, with a fortune equivalent to billions in today's currency.

However, the emergence of the new rich also led to significant social tensions. The lifestyles of the wealthy starkly contrasted with the struggles of the working class. The new rich often engaged in ostentatious displays of wealth, from grand mansions to lavish parties, which fueled resentment among the lower classes. This disparity highlighted the growing divide between the affluent and the impoverished, paving the way for social movements advocating for workers' rights and economic reform.

While the new rich thrived, millions of Americans faced harsh realities of poverty and poor living conditions. The rapid industrialization and urbanization of this era resulted in an influx of workers into cities, where they sought employment in factories and mills. However, the demand for labor often led to exploitative practices, including long working hours, low wages, and unsafe working environments.

Many workers lived in crowded tenements, often characterized by inadequate sanitation, poor ventilation, and a lack of basic amenities. These buildings were typically located in impoverished neighborhoods, where access to clean water and healthcare was minimal. The living conditions were dire, with entire families crammed into small, dark apartments, which contributed to the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis and cholera. The image of these tenements starkly contrasted with the luxurious homes of the wealthy, further accentuating the divide between classes.

Moreover, the economic system of the Gilded Age was marked by a lack of social safety nets. The government largely adhered to laissez-faire policies, allowing businesses to operate without significant regulation. As a result, there was little to no support for individuals facing economic hardships, further exacerbating the plight of the working class. Many families struggled to make ends meet, leading to a rise in child labor as children were forced to work in factories to contribute to their family's income.

Amidst the glaring wealth disparity and social issues, the Gilded Age also witnessed the rise of philanthropy as a response to the challenges faced by the less fortunate. Many of the era's wealthiest individuals felt a moral obligation to give back to society, leading to significant charitable contributions and the establishment of foundations. Andrew Carnegie, in particular, became a prominent advocate for philanthropy, famously declaring that "the man who dies rich dies disgraced." His belief in the “Gospel of Wealth” emphasized that the wealthy had a responsibility to use their fortunes to benefit society.

Carnegie's philanthropic efforts included the establishment of public libraries, educational institutions, and cultural organizations. His foundation funded the construction of over 2,500 public libraries across the United States, providing access to education and resources for millions. Similarly, John D. Rockefeller's philanthropy focused on healthcare and education, leading to the creation of institutions like the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Foundation.

However, the motivations behind philanthropy during the Gilded Age were often complex. While many viewed these donations as acts of benevolence, others criticized them as a means for the wealthy to maintain their influence and control over society. The concept of "philanthrocapitalism" emerged, where the wealthy used their financial power to shape social policies and priorities, raising questions about the effectiveness and ethics of such interventions.

The impact of philanthropy during the Gilded Age was profound, yet it also sparked debates about the extent to which wealthy individuals could and should address systemic social issues. While philanthropic contributions improved living conditions for some, they did not fundamentally change the underlying structures that perpetuated inequality.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| New Rich | Emergence of industrial tycoons; stark contrast in wealth and lifestyle compared to the working class. |

| Poverty | Poor living conditions; crowded tenements; lack of social safety nets and worker protections. |

| Philanthropy | Wealthy individuals contributing to societal needs; however, motivations and effectiveness questioned. |

The Gilded Age was a period marked by profound contradictions. While the new rich enjoyed unprecedented wealth, the majority of Americans faced challenges that highlighted the stark realities of poverty, exploitation, and inequality. The philanthropic efforts of the wealthy, while beneficial in many respects, were often viewed through a critical lens, raising important questions about responsibility, power, and the role of the wealthy in addressing social issues. These themes of wealth disparity and social justice would continue to resonate in American society, setting the stage for future reform movements and changes in policy.

The Gilded Age, spanning from the 1870s to the early 1900s, was not only a time of remarkable economic transformation but also a period rich in cultural developments and artistic expression. This era, marked by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and significant social change, greatly influenced American culture and the arts. Various movements emerged, reflecting the complexities of society and the diverse experiences of its people. In this section, we will explore literature and social commentary, the growth of mass entertainment, and architectural innovations and urban design that characterized this vibrant period in American history.

Literature during the Gilded Age served as both a mirror and a critique of the rapidly changing American society. As the country experienced unprecedented economic growth and social upheaval, authors such as Mark Twain, Henry James, and Edith Wharton emerged as prominent voices, addressing the complexities of modern life. Twain, often considered the father of American literature, used satire to expose the moral dilemmas and societal issues of the time. His novel "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" (1884) confronted themes of racism, identity, and the conflict between civilization and natural instincts.

Henry James, on the other hand, focused on the psychological and social intricacies of the American elite. His works, such as "The Portrait of a Lady" (1881), explored the struggles of individuals navigating the complexities of wealth and personal freedom. Through sophisticated character development and intricate plots, James highlighted the moral ambiguities of a society in transition.

Edith Wharton, a contemporary of James, delved into the lives of the upper class, providing sharp critiques of their pretensions and moral shortcomings. Her novel "The Age of Innocence" (1920), which won the Pulitzer Prize, is a poignant exploration of societal expectations and the constraints placed on individuals, particularly women, in the Gilded Age. Wharton's work exemplified the tensions between personal desire and social obligation, a recurring theme in literature during this period.

A significant trend in literature during the Gilded Age was the rise of realism and naturalism. Authors such as Stephen Crane and Frank Norris depicted the harsh realities of urban life and the struggles of the working class. Crane's novel "Maggie: A Girl of the Streets" (1893) painted a stark picture of poverty and social decay in New York City, while Norris's "McTeague" (1899) examined the brutalities of capitalism and human greed. These works challenged the romantic notions of the American Dream, revealing the darker undercurrents of society.

The Gilded Age witnessed the emergence of mass entertainment, transforming the landscape of American leisure. With the rise of urban centers and a burgeoning middle class, new forms of entertainment became accessible to a wider audience. One of the most significant developments was the proliferation of vaudeville theaters, where audiences could enjoy a variety of performances, from comedians to musicians to dancers.

Vaudeville, which gained popularity in the late 1880s, became the quintessential American entertainment experience. It was characterized by its diverse acts, which catered to all tastes and demographics. The format allowed for the inclusion of various cultural influences, reflecting the melting pot that America had become during the Gilded Age. Performers such as Eddie Cantor and Al Jolson became household names, and the shows often included elements of satire that critiqued societal norms.

In addition to vaudeville, the late 19th century saw the rise of the circus as a significant form of entertainment. P.T. Barnum's circus, later known as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, showcased exotic animals, acrobats, and various acts that captivated audiences across the nation. The circus represented a form of escapism, allowing Americans to experience a world of wonder and excitement amidst the challenges of daily life.

The invention of the motion picture in the late 1890s marked a pivotal moment in entertainment history. The first films were short and simple, but they quickly evolved into longer narratives that captured the imagination of the public. Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope and the Lumière brothers' Cinématographe were instrumental in popularizing cinema. By the early 1900s, nickelodeons emerged, offering affordable access to films and laying the groundwork for the future of the film industry.

Furthermore, the growth of the music industry during this period cannot be overlooked. The advent of the phonograph revolutionized the way people consumed music. Artists like Scott Joplin introduced ragtime music, which became a sensation across the country. Joplin's compositions, such as "Maple Leaf Rag," highlighted African American musical traditions and played a crucial role in the development of jazz and popular music in the decades to come.

As cities expanded and industrialized during the Gilded Age, architectural innovations and urban design transformed the American landscape. The skyline of cities like New York and Chicago began to reflect the ambitions of the era, with skyscrapers rising to new heights. The use of steel and reinforced concrete allowed for the construction of taller buildings, fundamentally changing urban architecture.

One of the key figures in this architectural revolution was Louis Sullivan, often referred to as the "father of skyscrapers." His design for the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, completed in 1891, is considered one of the first true skyscrapers. Sullivan's philosophy emphasized the importance of form following function, leading to the creation of buildings that were not only functional but also aesthetically pleasing.

In Chicago, the Great Fire of 1871 served as a catalyst for architectural innovation. The city rebuilt itself with a focus on modern design and infrastructure. The Chicago School of Architecture emerged, characterized by its use of steel frames, large windows, and minimal ornamentation. This movement laid the groundwork for the modernist architectural style that would dominate the 20th century.

Alongside skyscrapers, the Gilded Age also saw the rise of grand public buildings and monuments. The construction of the Chicago Auditorium Building, completed in 1889, exemplified the ambition of the period. Designed by Adler & Sullivan, this impressive structure combined a theater and hotel, showcasing the importance of cultural spaces in urban life.

Urban design during the Gilded Age was not solely focused on vertical growth; it also encompassed the creation of public parks and recreational spaces. The City Beautiful Movement emerged in response to the overcrowded and polluted urban environments. Advocates sought to enhance the quality of life in cities by incorporating green spaces, parks, and beautiful architecture. Central Park in New York City, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, was a precursor to this movement and served as a model for other cities seeking to improve urban living conditions.

As cities grew, issues of social inequality and poverty became increasingly visible. The juxtaposition of opulent mansions and impoverished tenements illuminated the stark disparities within urban environments. This tension prompted architects and urban planners to consider the social implications of their designs, leading to a greater emphasis on community-oriented spaces and social reform in the years to come.

In summary, the Gilded Age was a period of profound cultural developments and artistic expression. Literature served as a powerful medium for social commentary, while mass entertainment transformed leisure activities across the nation. Architectural innovations and urban design reflected the ambitions and challenges of a rapidly changing society. Together, these cultural facets shaped the identity of America during a time of significant transformation.