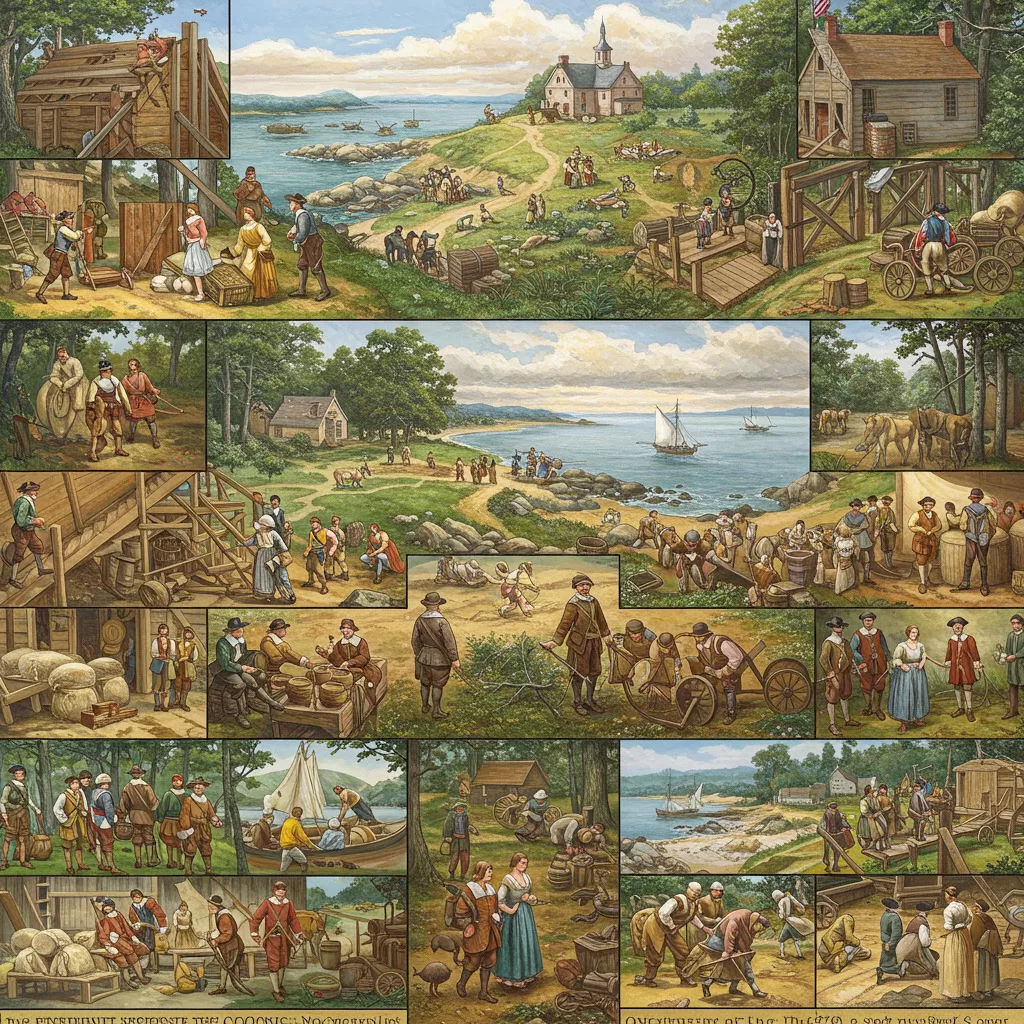

The establishment of the New England Colonies marks a significant chapter in the broader narrative of American history, characterized by a blend of ambition, faith, and resilience. As European powers sought new territories and opportunities in the 17th century, the New England region emerged as a focal point for settlement, driven primarily by the desire for religious freedom and economic prosperity. This period not only shaped the landscape of early America but also laid the groundwork for the diverse society that would evolve in the centuries to come.

Central to the establishment of these colonies was the influence of Puritanism, a movement that sought to reform the Church of England and create a "city upon a hill" that exemplified moral and spiritual ideals. Key figures, such as John Winthrop and Roger Williams, played vital roles in navigating the complexities of governance, community life, and relations with Indigenous peoples. Their stories and decisions reflect the challenges and triumphs faced by those who dared to forge a new life in an unfamiliar land.

In exploring the historical context, geographical features, and social developments of the New England Colonies, we uncover the intricate tapestry of life that defined this region. The interplay of faith, community, and economy not only shaped the identity of the Colonies but also set the stage for the evolving narrative of the United States as a whole.

The establishment of the New England colonies is a significant chapter in American history. These colonies were founded primarily for religious freedom, economic opportunities, and the pursuit of a better life. Understanding the historical context of the New England colonies involves delving into early European exploration, the pivotal role of Puritanism, and the key figures who influenced the establishment of this region. Each of these aspects contributed to the unique character and development of New England, setting the stage for its future impact on the United States.

The roots of European exploration in North America can be traced back to the late 15th century, with the voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Following Columbus, explorers from various European nations, including England, France, and Spain, began to navigate the Atlantic Ocean, seeking new trade routes and territories. In the early 1600s, England, motivated by both economic ambition and a desire for religious freedom, turned its attention to the New World.

One of the earliest attempts at establishing an English colony in America was the Roanoke Colony, established in 1585 on Roanoke Island in present-day North Carolina. However, this colony mysteriously disappeared by the late 1580s, leaving behind only the word "Croatoan" carved into a tree. Despite this setback, interest in colonization persisted, and the early 1600s saw more organized efforts to settle in North America.

The establishment of Jamestown in Virginia in 1607 marked a significant milestone for English colonization. However, the harsh conditions, conflicts with Indigenous peoples, and struggles for resources highlighted the challenges that settlers faced. In contrast, the New England colonies would emerge from a different set of motivations and circumstances, primarily driven by religious dissent and the search for a community that embodied their values.

In 1620, the Pilgrims, a group of English Separatists seeking freedom from the Church of England, established the Plymouth Colony. They sailed aboard the Mayflower and landed at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. This settlement was significant not only for its religious motivations but also for its early display of democratic governance through the Mayflower Compact, which established a framework for self-governance among the settlers.

Following the Pilgrims, the Puritans, seeking to purify the Church of England from within, also sought refuge in the New World. In 1630, a larger wave of Puritan settlers, led by John Winthrop, founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This colony would quickly become a model for future New England settlements, emphasizing the importance of community, religious conformity, and civic responsibility.

Puritanism played a crucial role in shaping the cultural and social fabric of New England. Emerging from the Protestant Reformation, Puritans sought to reform the Church of England and eliminate remnants of Catholicism. Their belief in predestination and the importance of personal piety led them to create tightly-knit communities where religious adherence was paramount.

The Puritans viewed their migration to the New World as a divine mission. They believed that by establishing a "city upon a hill," they would create a model society that would inspire others and demonstrate the virtues of their faith. This sense of purpose imbued their settlements with a strong moral and ethical framework, which influenced their laws, governance, and interactions with Indigenous peoples.

Education was also a priority for Puritans, who believed that reading the Bible was essential for personal salvation. This emphasis on literacy led to the establishment of schools and colleges, including Harvard College in 1636, the first institution of higher education in America. The Puritan commitment to education fostered a culture that valued knowledge and intellectual engagement, setting the stage for the later development of New England's educational institutions.

However, the Puritan belief system also had its drawbacks. Their stringent moral codes often led to intolerance of dissenting views and practices, as seen in the persecution of Quakers and the infamous Salem witch trials in the late 17th century. The Puritan legacy is thus a complex interplay of religious devotion, community cohesion, and the darker aspects of religious intolerance.

Several key figures played pivotal roles in the establishment and development of the New England colonies, each contributing to the region's unique identity. Among them, John Winthrop stands out as a central figure in the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony. Winthrop, a lawyer and devout Puritan, envisioned a society governed by Puritan principles. His famous sermon, "A Model of Christian Charity," articulated the idea of a collective mission to create a just and moral society.

Another important figure was Roger Williams, a religious dissenter who advocated for the separation of church and state. Williams' beliefs led him to found the colony of Rhode Island, which became a refuge for those seeking religious freedom. His vision of a pluralistic society would later influence the concept of religious tolerance in America.

An additional notable figure was Anne Hutchinson, a Puritan spiritual advisor who challenged the established religious norms of her time. Hutchinson's theological views and her criticism of the clergy led to her trial and subsequent banishment from Massachusetts Bay Colony. Her case highlighted the tensions between individual belief and communal orthodoxy, shaping the discourse on religious freedom in New England.

Other figures, such as Thomas Hooker, who founded the Connecticut Colony, and John Davenport, co-founder of New Haven Colony, contributed to the expansion of Puritan settlements. Each of these individuals helped to establish communities that reflected their interpretations of faith and governance, ultimately shaping the character of New England.

In summary, the historical context of the New England colonies is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of early exploration, religious fervor, and the influential figures who shaped their founding. The interplay of these elements laid the groundwork for the distinctive society that would emerge in New England, a society characterized by its commitment to community, governance, and religious principles.

The New England colonies, consisting of Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, emerged in the early 17th century as a distinct region of English colonization in North America. Understanding the geographical and economic features of these colonies is critical in appreciating their development and unique identity. The New England landscape, with its diverse geography and climate, played a significant role in shaping the economic activities and societal structures of these early settlements.

The geographic landscape of New England is characterized by its rugged terrain, abundant natural resources, and a climate that varies significantly from other regions of the United States. This area is defined by its coastal regions, rolling hills, forests, and mountain ranges, which influence both settlement patterns and economic pursuits.

New England's coastline stretches over 6,000 miles, featuring rocky cliffs, sandy beaches, and several natural harbors. The Atlantic Ocean provided essential resources, such as fish and shellfish, while facilitating trade and transportation. The region's extensive rivers, including the Connecticut and Merrimack, served as vital arteries for commerce and communication, allowing settlers to navigate and transport goods efficiently.

Inland, the topography is marked by the Appalachian Mountains, which run through the western part of the region. The presence of forests offered timber, a crucial resource for building homes and ships, as well as for fuel. The soil quality varies, with some areas having fertile land suitable for agriculture while others are less hospitable for farming. As a result, New England's settlers had to adapt their farming practices to the challenging conditions, often relying on subsistence farming and crop rotation.

The economy of the New England colonies was diverse and multifaceted, shaped by the region's geography, climate, and available resources. Unlike the Southern colonies, which primarily relied on plantation agriculture, New England's economy was more focused on trade, fishing, and small-scale farming.

Fishing was a cornerstone of the New England economy. The Atlantic waters provided an abundance of fish, including cod, haddock, and mackerel. Fishing not only supplied food for the local population but also became a significant export. The cod fishery, in particular, was a lucrative enterprise, establishing New England as a central player in the transatlantic trade networks. Fishermen often braved the harsh ocean conditions, using small boats to reach rich fishing grounds.

In addition to fishing, shipbuilding emerged as a vital industry in New England. The region's abundant timber resources allowed for the construction of sturdy ships, which were essential for fishing, trade, and transportation. Shipyards flourished in coastal towns like Salem and Portsmouth, where skilled craftsmen built vessels that became integral to the colonial economy.

Trade was another significant economic activity in the New England colonies. Towns developed into bustling ports, facilitating commerce with Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. Merchants engaged in the triangular trade, exporting fish, timber, and rum while importing goods such as sugar, molasses, and manufactured items. The economic interdependence of the colonies with international markets fostered a sense of entrepreneurship and innovation among the settlers.

Agriculture, while not the primary economic driver, played a role in the sustenance of the New England colonies. Farmers cultivated crops such as corn, beans, and squash, often referred to as the "Three Sisters." The harsh winters limited the growing season, leading to the practice of subsistence farming, where families produced just enough food to meet their needs. Livestock, including cattle, pigs, and poultry, supplemented diets and provided additional resources.

The New England colonies were interconnected through extensive trade networks, both among themselves and with other regions. The geography of New England, with its natural harbors and navigable rivers, facilitated the movement of goods and people, contributing to the growth of commerce.

Within the colonies, trade flourished between towns. Coastal settlements exchanged fish and timber with inland communities that provided agricultural products. The development of towns such as Boston, Newport, and New Haven as trade centers allowed for the establishment of markets and the exchange of goods. These towns became cultural and economic hubs, fostering a sense of community and shared identity among the settlers.

On a broader scale, New England engaged in international trade, establishing economic relationships with Europe and the West Indies. The region's merchants actively participated in the triangular trade, exchanging goods for enslaved individuals in Africa and importing sugar and molasses from the Caribbean. This trade not only enriched the colonial economy but also reflected the complexities of colonial society, where economic interests often intersected with moral dilemmas surrounding slavery.

The trade networks also led to the emergence of a merchant class that wielded significant economic power and influence. Wealthy merchants invested in shipping and trade ventures, accumulating capital that allowed them to shape local politics and society. The economic prosperity of the New England colonies contributed to a growing sense of identity distinct from that of England, laying the groundwork for the eventual drive toward independence.

Key Economic Activities in New England Colonies:In conclusion, the geographical and economic features of the New England colonies were instrumental in shaping their development. The rugged landscape, coupled with a diverse economy based on fishing, trade, and small-scale agriculture, fostered a unique colonial identity. The interconnected trade networks not only enriched the region economically but also laid the foundation for the emergence of a distinct American culture, setting the stage for future historical developments.

The establishment of the New England colonies was not merely a political and economic venture; it was also deeply intertwined with social and cultural developments that shaped the region's identity. The New England colonies, primarily founded by Puritan settlers, were characterized by their emphasis on community, governance, education, religion, and their complex interactions with Indigenous peoples. This section delves into these aspects, revealing how they contributed to the unique tapestry of New England society.

Community life in the New England colonies was heavily influenced by Puritan ideals, which prioritized a close-knit social structure. Settlements were often organized around congregational churches, which served not only as places of worship but also as centers for community gatherings and governance. This unique blend of church and state meant that the church played a pivotal role in everyday life, with attendance at services being mandatory. The Puritan belief in a "city upon a hill" fostered a sense of collective identity and responsibility, creating a society in which communal values were paramount.

Governance in the New England colonies was characterized by a mix of democratic principles and religious authority. Town meetings were a common form of local governance, allowing male property owners to participate directly in decision-making processes. This form of governance was revolutionary for its time, as it provided a platform for community members to voice their opinions and influence the direction of their towns. However, it is important to note that this system was not inclusive; women, Indigenous peoples, and enslaved individuals were largely excluded from these political processes.

As communities grew, the need for more structured governance became apparent. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, for instance, adopted a formal legal code known as the Body of Liberties in 1641, which outlined the rights of individuals and the responsibilities of government. This document was revolutionary in its acknowledgment of certain civil liberties, such as due process and the right to a fair trial, although it still reflected the Puritan ethos that prioritized order and moral behavior over individual freedom.

Education was highly valued in New England, primarily as a means to ensure that individuals could read the Bible and engage with religious teachings. The Puritans believed that literacy was essential for personal faith and moral living, leading to the establishment of schools and educational institutions. The first public school in the colonies, the Boston Latin School, was founded in 1635, highlighting the importance placed on education for boys, while girls were often educated at home to focus on domestic skills.

In 1647, the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the Old Deluder Satan Act, which required towns with a certain population to establish a grammar school. This law was significant as it underscored the Puritan commitment to education and the idea that an informed populace was necessary to combat ignorance and sin. The emphasis on education paved the way for later developments in higher education, leading to the founding of prestigious institutions such as Harvard College in 1636, which was established to train clergy as well as educated citizens.

Religion was the cornerstone of New England life, with Puritanism shaping every aspect of society. The strict moral code upheld by Puritans dictated social behavior, influencing everything from family dynamics to legal systems. The colonies were marked by a strong sense of religious conformity, which, while fostering a cohesive community, also led to tensions and conflicts with those who held differing beliefs. Dissenters, such as Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, challenged the established religious order, ultimately leading to their expulsion from Massachusetts and the founding of new colonies like Rhode Island, which offered greater religious freedom.

The arrival of European settlers in New England marked the beginning of complex and often fraught interactions with Indigenous peoples. Initially, there were instances of cooperation, as settlers relied on Native American knowledge of the land for survival. The Wampanoag tribe, led by Chief Massasoit, notably assisted the Pilgrims during their first winter, leading to the famous Thanksgiving celebration in 1621. This early cooperation was rooted in mutual benefit, as the Indigenous peoples sought to maintain their way of life while the settlers aimed to establish their presence in the New World.

However, as more settlers arrived and colonial expansion intensified, relationships soured. The increasing demand for land led to the displacement of Indigenous communities, resulting in a series of conflicts, notably King Philip's War (1675-1676). This brutal conflict, named after the Wampanoag leader Metacom, saw Indigenous warriors and colonial militias clashing violently. The war resulted in significant loss of life on both sides and marked a turning point in the power dynamics between Indigenous peoples and European settlers, leading to the near destruction of several Native American tribes in New England.

Despite the conflicts, cultural exchanges continued. The introduction of European goods, such as metal tools and firearms, transformed Indigenous ways of life, while Native American agricultural practices, such as the cultivation of corn and beans, influenced colonial farming methods. These interactions contributed to a unique cultural landscape in New England, where both European and Indigenous customs coexisted, albeit often uneasily.

In summary, the social and cultural developments in the New England colonies were shaped by a myriad of factors, from Puritan religious beliefs to community governance and interactions with Indigenous peoples. The emphasis on education and a communal way of life fostered a distinct identity that would influence the future trajectory of the United States. The legacy of these early social structures, governance models, and cultural exchanges continues to resonate in contemporary American society, highlighting the importance of understanding this foundational period in history.