The Great Depression, a period marked by unprecedented economic turmoil in the United States, gave rise to a phenomenon that would symbolize the struggles of countless individuals and families: Hoovervilles. These makeshift shantytowns emerged as a direct response to widespread unemployment and the crippling effects of poverty, providing a temporary refuge for those who had lost everything. Named derisively after President Herbert Hoover, who many blamed for the economic crisis, these communities became a poignant reminder of the desperate measures people took to survive during one of the darkest chapters in American history.

In the shadow of crumbling fortunes and shattered dreams, Hoovervilles were not just mere collections of tents and shacks; they represented the resilience and determination of the human spirit. Amidst the harsh realities of life in these encampments, residents forged new social bonds and communities, navigating the challenges of inadequate housing, sanitation, and health issues. Understanding the emergence, living conditions, and lasting impact of Hoovervilles offers crucial insights into the broader narrative of the Great Depression and the evolution of American society during this turbulent time.

The emergence of Hoovervilles during the Great Depression serves as a poignant reminder of the economic devastation that swept across the United States in the late 1920s and 1930s. Named derisively after President Herbert Hoover, who was in office when the Depression struck, these makeshift communities symbolized the struggles faced by millions of Americans who lost their homes, jobs, and savings. Understanding the definition and origins of Hoovervilles, the historical context of the Great Depression, and the role of Herbert Hoover provides insight into this significant period in American history.

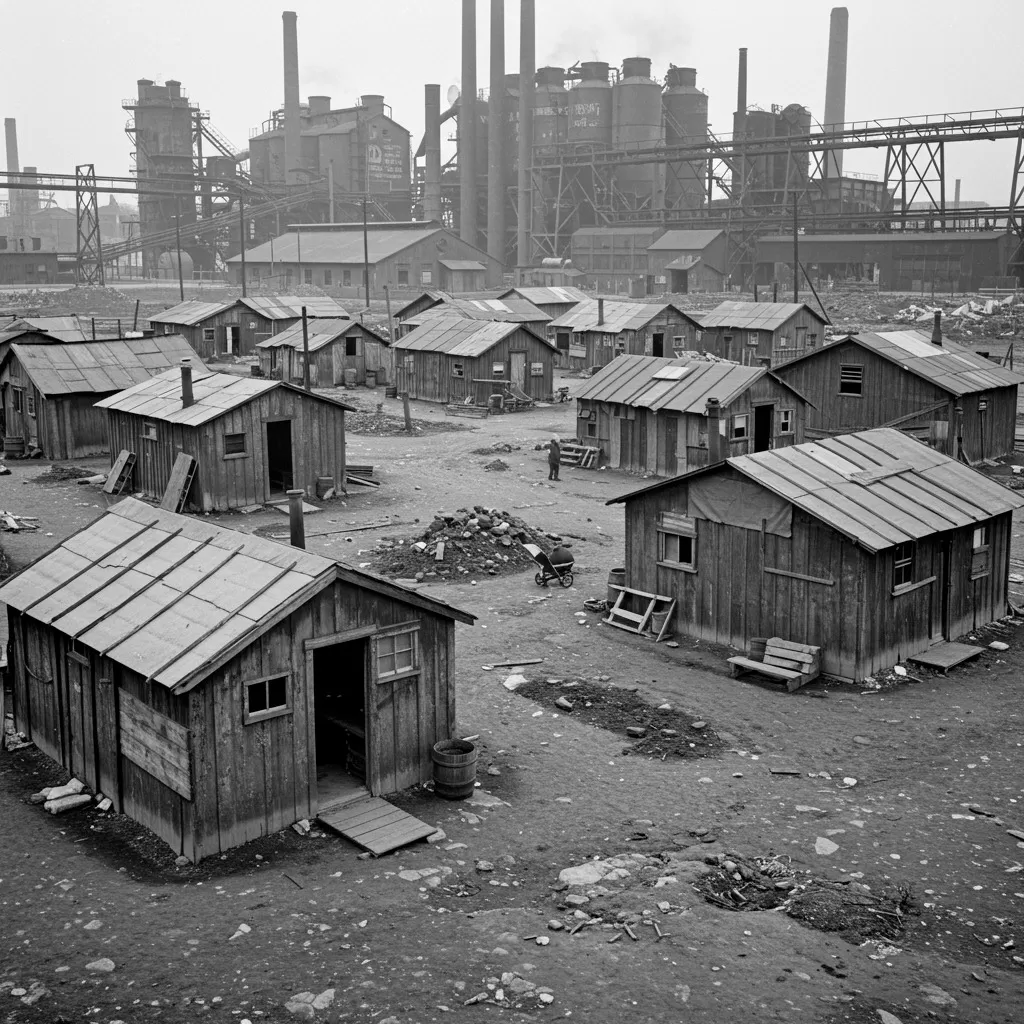

Hoovervilles were informal settlements or shantytowns constructed by the homeless in urban areas across the United States during the Great Depression. These communities emerged as a direct response to the widespread economic despair that left many families without housing. The term "Hooverville" was coined by the homeless as a way to express their frustration with President Hoover's perceived inaction and indifference toward their plight. The shantytowns were typically made from scrap materials such as cardboard, wood, and metal, reflecting the resourcefulness of their inhabitants.

While the term "Hooverville" is most commonly associated with the shantytowns of the 1930s, similar informal settlements had existed prior to the Depression. However, the scale and visibility of Hoovervilles during this time were unprecedented. As the stock market crashed in October 1929 and the economy spiraled downward, the number of homeless individuals and families skyrocketed. By the early 1930s, major cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco saw the rapid growth of these encampments, which became a common sight across the nation.

To fully comprehend the emergence of Hoovervilles, one must consider the historical context of the Great Depression. The stock market crash of 1929 marked the beginning of a decade-long economic downturn characterized by mass unemployment, deflation, and widespread poverty. As banks failed and businesses closed, millions of Americans found themselves out of work and unable to provide for their families. The unemployment rate soared to nearly 25% by 1933, leaving a staggering number of individuals without the means to afford basic necessities, let alone stable housing.

The Great Depression was exacerbated by a series of factors, including the failure of the agricultural sector, which was already suffering from the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. Crops failed, and farmers were unable to sustain their livelihoods, leading to an influx of displaced individuals seeking work and shelter in urban areas. As cities became overwhelmed with the growing population of unemployed and homeless, the formation of Hoovervilles became an inevitable response to the dire circumstances.

The societal impact of the Great Depression was profound. Traditional family structures and community bonds were strained as fathers and mothers struggled to find work and provide for their children. Many families were forced to split up, with some members traveling to different parts of the country in search of opportunities. The pervasive sense of hopelessness and despair was reflected in the very fabric of Hoovervilles, where people from diverse backgrounds came together in a shared struggle for survival.

Herbert Hoover's presidency, which lasted from 1929 to 1933, was marked by his response to the economic crisis that enveloped the nation. Initially, Hoover believed that the economy would self-correct and that government intervention would not be necessary. This philosophy of limited government intervention and reliance on voluntary actions by businesses was deeply rooted in his belief in individualism and self-reliance.

As the economic situation worsened, Hoover's administration took some steps to address the crisis, but these measures were often seen as insufficient. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation, established in 1932, aimed to provide emergency loans to banks and businesses, but it did little to alleviate the suffering of ordinary citizens. Hoover's reluctance to provide direct relief to the unemployed and homeless led to widespread criticism, and as a result, he became a symbol of governmental failure during the Great Depression.

The term "Hooverville" emerged as a direct critique of his presidency, encapsulating the frustration and anger of those who felt abandoned by their government. The shantytowns reflected not only the dire living conditions of their residents but also the broader discontent with Hoover's policies. As people sought refuge from the harsh realities of unemployment and homelessness, they found themselves living in makeshift shelters that were often devoid of basic amenities.

Despite the harsh living conditions, Hoovervilles also became a space for community and resilience. Residents banded together to support one another, sharing resources and forming social networks that provided emotional and practical assistance. This sense of solidarity was essential for survival in an environment characterized by desperation and uncertainty.

In conclusion, the emergence of Hoovervilles is a significant chapter in the narrative of the Great Depression. Understanding their definition and origins, the historical context of the economic crisis, and the role of Herbert Hoover provides valuable insights into the challenges faced by millions of Americans during this tumultuous period. The legacy of Hoovervilles continues to resonate today, serving as a reminder of the importance of social safety nets and the need for compassionate government responses in times of crisis.

The Great Depression, a period characterized by economic turmoil and widespread unemployment, birthed numerous makeshift communities known as Hoovervilles. These shantytowns were emblematic of the struggles faced by countless Americans during this era. Within these communities, the living conditions varied significantly, shaped by the resources available to the inhabitants and the social dynamics that emerged in response to adversity. This section delves into the housing structures and materials used in Hoovervilles, the community life and social dynamics among residents, and the health and sanitation challenges that these makeshift towns faced.

Hoovervilles were often constructed from whatever materials could be scavenged or repurposed. Residents utilized a mix of cardboard, scrap wood, metal, and other discarded materials to create rudimentary shelters that provided minimal protection against the elements. The structures varied in size and complexity, ranging from simple shacks to more elaborate constructions built to accommodate larger families. As residents faced the challenges of building their homes, creativity and resourcefulness became essential traits.

Many Hoovervilles were located in urban areas, often on vacant lots or along riverbanks. The site selection was influenced by several factors, including proximity to work opportunities, access to water sources, and the relative safety of the location. Some of the largest Hoovervilles were found in cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. In these urban centers, the concentration of displaced individuals led to a more significant community presence, where structures were built closely together, fostering a sense of solidarity among residents.

The construction techniques used in Hoovervilles were often rudimentary. Residents fashioned walls from wooden pallets and roofing from tin or tar paper. Insulation was a luxury that few could afford, leading to uncomfortable living conditions, especially during harsh winters or scorching summers. Despite the lack of proper infrastructure, residents took pride in their makeshift homes, often personalizing them with decorations or communal spaces to foster a sense of belonging.

Life in Hoovervilles was characterized by a unique blend of hardship and resilience. The social dynamics within these communities were shaped by shared experiences of poverty and displacement, fostering a strong sense of camaraderie among residents. As families came together to navigate their struggles, they formed tight-knit networks that provided emotional and practical support. This sense of community was vital in coping with the daily challenges posed by life in a Hooverville.

Daily routines in Hoovervilles often revolved around survival. Many residents sought work in nearby factories or farms, while others relied on bartering for goods and services. Community kitchens were established in some Hoovervilles, where residents could share meals and resources. These communal efforts not only alleviated hunger but also reinforced social bonds among families facing similar hardships.

In addition to the practical aspects of community life, social activities played a crucial role in maintaining morale. Residents organized events such as music nights, storytelling sessions, and gatherings for children, creating moments of joy amid the struggles. These activities served as a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit, fostering hope and solidarity in the face of adversity.

However, Hoovervilles were not without their challenges. Tensions sometimes arose due to competition for limited resources, leading to conflicts between residents. Moreover, the stigma attached to living in a Hooverville often exacerbated feelings of isolation and shame among inhabitants. Despite these challenges, the spirit of community often prevailed, with residents working together to address issues and improve their living conditions.

The health and sanitation conditions in Hoovervilles were dire, exacerbated by the lack of infrastructure and resources. Many residents lacked access to clean water, and sanitation facilities were virtually non-existent. Public health issues were rampant as diseases spread quickly within the cramped quarters of these shantytowns, where families often lived in close proximity to one another.

Common ailments included respiratory infections, gastrointestinal diseases, and skin conditions, all of which were exacerbated by poor living conditions. The absence of adequate waste disposal systems led to unsanitary environments, contributing to the spread of illness. The lack of access to healthcare further complicated the situation, with many residents unable to afford medical attention or transportation to clinics.

Community members often took it upon themselves to address these health challenges. Some organized informal health clinics within their communities, where individuals with medical knowledge could provide basic care and advice. These grassroots efforts illustrated the resilience of residents and their commitment to supporting one another in times of crisis.

Despite the challenges, the plight of Hooverville residents garnered attention from the public and media. This visibility led to increased advocacy for government intervention and relief efforts. While many residents suffered in silence, the stories and struggles of those living in Hoovervilles eventually reached the broader American consciousness, contributing to a growing awareness of the need for social reform and assistance during the Great Depression.

Living conditions in Hoovervilles reflect the broader struggles of Americans during the Great Depression. The resilience and ingenuity of residents in the face of adversity highlight the human capacity to adapt and create community in challenging circumstances. Despite the overwhelming difficulties, the bonds formed in these shantytowns became a testament to the strength of the human spirit. The legacy of Hoovervilles serves as a poignant reminder of the importance of social support and community in times of crisis.

The Great Depression, spanning from 1929 to the late 1930s, was a period of profound economic turmoil in the United States, during which millions faced unemployment, poverty, and homelessness. One of the most visible manifestations of this crisis was the emergence of Hoovervilles—makeshift shantytowns named derisively after President Herbert Hoover, who was blamed for the economic collapse. The impact and legacy of Hoovervilles extend far beyond their immediate existence, influencing public perception, government policy, and the collective memory of a nation grappling with economic despair.

Hoovervilles became symbols of the suffering endured by ordinary Americans during the Great Depression. Initially, media coverage varied; some outlets portrayed these encampments as a necessary response to the economic disaster, while others emphasized the degradation and despair associated with life in such conditions. Publications like The New York Times and Life Magazine featured poignant photographs and stories that captured the stark realities faced by residents of Hoovervilles. Images of families huddled in substandard housing and children playing in dirt underscored the dire straits of the time.

As the media began to focus more on these communities, public perception shifted. Hoovervilles, once viewed simply as a refuge for the homeless, became emblematic of government failure. Editorials began to criticize Hoover's administration for its inadequate response to the crisis. The term "Hooverville" itself became synonymous with hardship, leading to a broader cultural narrative that questioned the efficacy of capitalism and the responsibility of government to care for its citizens.

Prominent figures, including photographers such as Dorothea Lange, played a crucial role in shaping public perception. Lange’s work, particularly her photograph "Migrant Mother," brought the struggles of impoverished families to the forefront of American consciousness. These images portrayed not just despair but also resilience, as families banded together to survive in the face of adversity. This nuanced portrayal contributed to a growing empathy for the plight of those living in Hoovervilles, leading to increased public support for government intervention and relief efforts.

The overwhelming visibility of Hoovervilles prompted a response from the federal government, albeit a delayed one. Initially, the Hoover administration was reluctant to intervene directly in the economy or provide extensive relief, adhering to a belief in limited government intervention. However, as the situation worsened and public outcry grew, the administration was forced to take action.

In 1932, the Federal Home Loan Bank Act was passed to help homeowners avoid foreclosure, and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation was established to provide financial support to banks and companies. However, these measures were often criticized as too little, too late. Instead, they mostly benefited large corporations rather than individuals struggling in Hoovervilles.

With the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and the subsequent New Deal programs, a more robust response was initiated. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) aimed to provide jobs and rebuild infrastructure, which indirectly helped many who lived in Hoovervilles. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) also began to provide direct assistance to those in need, offering food, shelter, and work programs, effectively addressing some of the immediate needs of the Hooverville residents.

Despite these efforts, many Hoovervilles remained throughout the 1930s, serving as a stark reminder of the economic struggles faced by millions. The persistence of these communities highlighted the inadequacies of the initial responses and the need for comprehensive reform in housing policies and social welfare systems.

The existence of Hoovervilles and the broader context of the Great Depression had a lasting impact on housing policies in the United States. The failures observed during this period prompted a reevaluation of how the government approached issues of poverty, housing, and urban development.

In the immediate aftermath of the Great Depression, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was established in 1934 to facilitate home ownership and improve housing standards. The FHA aimed to provide insurance for mortgage loans, making it easier for lower-income individuals to own homes. This marked a significant shift in federal policy, acknowledging the government's role in ensuring safe and affordable housing for its citizens.

Moreover, the experiences of those living in Hoovervilles influenced the development of public housing programs in the 1930s and 1940s. The United States Housing Authority was created in 1937, which led to the construction of public housing projects across the country. These initiatives aimed to eliminate slum conditions and provide quality housing to low-income families, in stark contrast to the makeshift shelters of Hoovervilles.

While these policies were a direct response to the failures highlighted by the existence of Hoovervilles, they also laid the groundwork for future housing legislation. The War on Poverty in the 1960s and subsequent housing policies continued to evolve, often referencing the lessons learned from the experiences of the Great Depression. The legacy of Hoovervilles is thus interwoven with the ongoing struggle for adequate housing and economic security in America.

| Year | Event/Policy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Reconstruction Finance Corporation | Provided financial support to banks and businesses, but limited direct aid to individuals. |

| 1932 | Federal Home Loan Bank Act | Helped homeowners avoid foreclosure but did not address the needs of the homeless directly. |

| 1933 | Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) | Provided jobs for young men and helped improve infrastructure. |

| 1935 | Works Progress Administration (WPA) | Created jobs in various sectors, indirectly aiding those in Hoovervilles. |

| 1937 | United States Housing Authority | Established to improve housing standards and eliminate slums. |

The legacy of Hoovervilles is also reflected in the ongoing discussions about homelessness and housing insecurity in contemporary America. The lessons learned during the Great Depression continue to resonate, as many communities still grapple with issues of poverty and inadequate housing. Furthermore, the historical context of Hoovervilles serves as a reminder of the importance of government intervention in times of economic crisis, shaping the debate on social safety nets and the role of public policy in ensuring the welfare of citizens.

In summary, the impact and legacy of Hoovervilles during the Great Depression were profound and multifaceted. These shantytowns not only highlighted the struggles of the era but also spurred significant changes in public perception, government policy, and the future of housing in America. As the nation continues to face challenges related to poverty and homelessness, the lessons from Hoovervilles remain crucial in understanding the complexities of economic hardship and the necessity of a compassionate response from society and government alike.